Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

Notes on Karl Grune's Die Straße (The Street)

Stefan Drössler

Die Straße (The Street / La Rue / La Strada)

(Germany 1923)

Directed, written and produced by Karl Grune

Photography by Karl Hasselmann

Set Design by Karl Görge, Ludwig Meidner

Cast: Eugen Klöpfer (The Husband), Lucie Höflich (His Wife), Leonhard Haskel (The

Gentleman from the Province), Aud Egede Nissen (The Girl), Hans Trautner (The Fellow),

Max Schreck (The Blind Man), Anton Edthofer (His Son), Sascha (The Child)

Production Company: Sternfilm GmbH

Distributed by: Ufa

Release Date: 29 November 1923 (U.T. Kurfürstendamm, Berlin)

Trailer for Die Straße (5 min.)

Today Karl Grune (1890-1962) is one of the lesser-known directors of German silent film, but he was once placed by contemporary critics in the forefront of European film artists. He owes this above all to Die Straße, which is considered his most important work. Siegfried Kracauer published two reviews upon its Frankfurt premiere, and repeatedly cited it in his writings as a key film, which founded the “street film” genre. In his book From Caligari to Hitler, he defines the “street film” as an allegory for German society’s slide into dictatorship: “The leading character breaks away from the social conventions to grasp life, but the conventions prove stronger than the rebel and force him into either submission or suicide.” Contemporary foreign critics praised the film’s technical qualities. In Kinematograph Weekly (17.01.1924), Lionel Collier called Die Straße “a milestone in the progress of screen technology and art”. Grune was considered progressive and innovative because he knew how to use the peculiarities of film. He explained his ideas in his essay Der Film ist Bewegungskunst [Film Is the Art of Movement] (Dortmunder Zeitung, Nr. 570, 05.12.1924): “What the stage expresses through words, the film must make clear through movement alone; it must try to eliminate the word as a means of communication. The image cannot be an empty illustration of the intertitles, it must be able to make the action process intelligible through its own arrangement. As music is a harmony of tones, so film should be a symphony of light, and just as music can be enjoyed even by the layman, so film should be enjoyed even by the spectator who does not understand the plot.”

In fact, the story of a little bank clerk who allows himself to be drawn into the seductive hustle and bustle of the city’s nightlife by the shadows cast through the window onto the ceiling of his apartment provides the framework for a parallel panorama of nameless protagonists, identified in the opening credits only as “The Gentleman from the Provinces”, “The Girl”, “The Fellow”, “The Blind Man”, or “The Child”. The actors use exaggerated gestures that make explanatory titles unnecessary. The few intertitles contain dialogue lines that are actually superfluous, and seem almost ironic in their simplicity.

Just as stylized as the acting are the film’s decor and buildings, made entirely in the studio. Karl Görge (1872-1933) constructed them in reduced perspective. An article in the newspaper B.Z. am Mittag (15.07.1923) described the three-dimensional models: “The road was built on the E.F.A. site in Steglitz, 75 metres long. Of course, it should give the viewer the impression of a much longer street. It begins at the front with a skyscraper 26 metres high (with a lighted café, ballroom, etc.), and then shrinks in height and width to very small three-dimensional house models, creating the illusion of considerable distance through their differences in size. This mathematical, very precisely calculated technique is again a completely new step in German film.” The sets were designed by the painter Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966), famous for expressive portraits and apocalyptic city visions. In his essay Anleitung zum Malen von Großstadtbildern [An Introduction to Painting Big Cities] in: Kunst und Künstler, XII, 1914, Meidner wrote: “A street does not consist of tonal values, but is a bombardment of hissing rows of windows, whizzing beams of light among vehicles of all kinds, and thousands of bouncing balls, fragments of people, billboards, and booming, shapeless masses of colour.” Cinematographer Karl Hasselmann (1883-1966) tried to visualize the chaos to which the petty bourgeois of the framing story feels exposed, using multiple exposures and image rotations, helping to realize the vision that Karl Grune emphasized in interviews: “I first see the milieu

and then approach the dramatic motif. Developing my new film Die Straße, I saw – yes, I saw – at first only the optical noise of a cosmopolitan street, its gleaming, glittering, its fever.” (Karl Grune: Film, nicht Literatur! [Film, not Literature!], Der Filmbote, Nr. 44, 03.11.1923)

Another innovation used to promote the film was the omission of intermissions. “The wordless, non-stop film. A very successful experiment, if not completely satisfactory,” wrote the critic of the trade journal Der Film (Nr. 48, 01.12.1923). Karl Grune was determined to break away from literary drama: “In my new film Die Straße, I have now tried to manage without Act divisions. From the outset, the plot is structured with complete temporal and spatial closure that is not ruptured. Mind you, I don’t want to elevate the film without Act divisions into an artistic principle. It seems to me that, given the assumptions of the manuscript, the progress we must strive for to avoid the danger of rigid form lies in uninterrupted action, to strengthen the unity of the plot.” (Karl Grune: Ohne Akte, B.Z. am Mittag, Nr. 148, 30.03.1923) Unfortunately, it is not known how this was technically achieved in cinemas with only one projector, which used the breaks between Acts to change reels. Contemporary critics were very skeptical, and could not imagine non-stop screenings of longer length. Otto Ernst Hesse wrote in Der Kinematograph (Nr. 877, 09.12.1923): “In the theatre of words, half an hour, at most three-quarters of an hour, is considered the maximum attention span one can expect from an audience. Rapid tempo in film cannot increase this maximum, but at most only reduce it, since within a certain period of time significantly more numerous and more intense emotions are triggered in the viewer than in the theatre of words.”

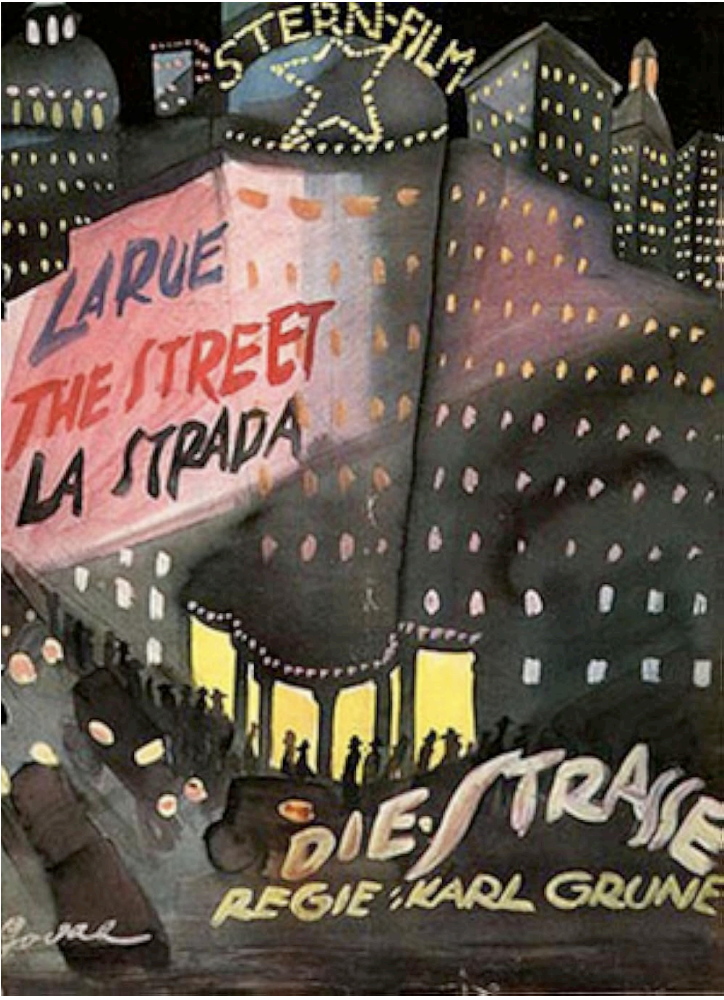

Just a few weeks after the film’s Berlin premiere on November 29, 1923, it was already released in London and Paris. From the outset, the production had been designed with international distribution in mind; at the time of accelerating German inflation, foreign sales against hard currencies were a profitable business. The original multi-colour poster for the film’s German premiere designed by illustrator and caricaturist Erich Godal (1899-1969) featured the title in four languages: Die Straße, The Street, La Rue, La Strada. The only insert in the film, a cheque held in the hands of the protagonist, is written in English. This internationality was by no means regarded positively by all the critics. “M.J.” of the Vossische Zeitung (Nr. 568, 01.12.1923) wrote: “It is depressing that this wealth of German ability has to be smuggled in abroad, so to speak, down the backstairs. No inscription on the street signs is dared, the policemen, clean-shaven, with foreign caps, deny their fatherland, just so no spectator on the Hudson or Thames turns up their noses. It certainly wasn’t pretty when Germany got carried away, but it’s embarrassing to see it duck.”

Despite the film’s universal design, it was altered in foreign export and distribution. New titles were introduced, storylines shortened, or intertitles omitted entirely because they were not essential to understand the plot. In 1947 the Museum of Modern Art produced a dupe negative from a slightly abridged nitrate copy of an English version, and the State Film Archive of the GDR produced a dupe negative with recreated German intertitles in the 1970s. This digital reconstruction by the Filmmuseum München draws on fragments of two Russian nitrate copies, one of them still showing traces of the original tints. Missing parts were supplemented by scenes from a duplicate negative provided by the Bundesarchiv. The titles were reconstructed from the German censorship card, dated 10 October 1923.

Stefan Drössler

Restoration Credits

Production: Filmmuseum München in collaboration with Gosfilmofond and Bundesarchiv

supported by Sunrise Foundation and Münchner Filmzentrum

Concept and Supervision: Stefan Drössler

Image Restoration: Christian Ketels, Stefan Wimmer

Score composed and performed by Günter A. Buchwald

Recording: Gunther Bittmann

Format: DCP, 4:3, tinted

Length: 2.057 Meter, 79 minutes (23 fps)

Premiere: 11 October 2023, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto Pordenone