Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

Love Has (No) Laws: Queer Weimar Cinema Across Borders

So Mayer

As the doctor in Anders [als die Andern] tells Paul’s parents: “It is neither a vice nor a crime, nor even a sickness, but a variation, one of the borderline cases in which nature is so rich.”

— Richard Dyer, 20.

Richard Dyer’s 1990 path-breaking article “Less and More than Women and Men: Lesbian and Gay Cinema in Weimar Germany” definitively added the complex nexus of genders and sexualities to the rich field of Weimar cinema studies.[1] Dyer offers a dual historical evaluation that places film critical writing on Anders als die Andern (Richard Oswald, 1919) and Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1932) and contemporaneous sexological, sociological and popular understandings of gender and sexuality side by side, showing the gap between the appraisal of the films and their place in a cultural continuum of queerness. His meticulous research and exquisite readings implicitly demonstrate both the lack of lesbian and gay film criticism on Weimar cinema, at the time and subsequently; and the value of queer film scholarship – that is, film scholarship formulated in tandem with queer theory – for giving the fullest reading of Weimar cinema as an aesthetic, formal, social and political formation. As B. Ruby Rich wrote in her 1981 re-evaluation of Mädchen for Jump Cut (one of Dyer’s key sources and precursors), “In this reading, the film remains a profoundly anti-fascist drama. But now its political significance becomes a direct consequence of the film’s properly central subject (of lesbianism) rather than a covert message wrapped in an attractive but irrelevant metaphor.”[2] As Rich argues, the film’s heralded visual, aural and gestural aesthetics, blending Expressionism with the influence of Soviet montage, is an “attractive but [not] irrelevant” wrapping, a part of its political radicalism focused through its central subject of queerness and genderqueerness.

Four decades on from Rich’s article and three decades on from Dyer’s, I choose to use the word ‘queer’ to recognize an overarching complexity that his article identifies: that of the relation between sexuality and gender in Weimar sexology and popular culture through the concept of inversion. Long-discredited, the term ‘invert’ has recently been re-evaluated by queer and trans scholars and activists, for example in the title of the short-lived Marxist gender abolitionist Invert Journal (2020-21).[3] Popular historians of gender and sexuality such as Hugh Ryan, in When Brooklyn Was Queer, and Kit Heyam, in Before We Were Trans, have looked carefully at the late 1920s and early 1930s as a key moment of formation of lesbian and gay identities as sexual in opposition to or separation from trans and genderqueer or non-binary identities as gendered, while also demonstrating the considerable latitude and overlap that existed within concepts of gender and sexuality in Weimar and American sexologies.[4] Thus Dyer’s outlining of the ways in which Anders exemplifies the ideological struggle between the straight-acting homonationalist gay formulated by Adolf Brand, and the ‘third sex’ of Magnus Hirschfeld’s early book on Berlin opens the film up to a queer and trans, as much as gay, reading: a ‘more than women and men’, to paraphrase his title.[5]

Within the field of cultural studies, I also want to signal how the films discussed, and the ways in which they have been discussed post-Dyer, queer (verb) Weimar cinema. In line with contemporary critiques of 1990s queer theory as privileging a white Eurowestern universalism and a subsequent shift rightward within US white lesbian and gay communities into homonationalism, I also use ‘queer as in fuck you’, a slogan of unknown origin but, as transfeminist legal scholar Florence Ashley jokes, one that upholds the radical sense that “queer means anyone who isn’t straight and is sexually attracted to communism.”[6] Building on Dyer’s arguments concerning the political stances expressed in the two queer classics of Weimar cinema, particularly the challenge to Paragraph §175 in Anders and the queer anti-fascism of Mädchen, I argue for the political radicalism of queerness in these films and those associated with them going beyond and through radical gender and sexuality toward a radical anti-nationalism that crossed and challenged borders as well as sodomy laws.

The 2016 restoration of Anders by Jan-Christopher Horak for Outfest, and the 2020 restoration of Hirschfeld’s campaigning documentary Gesetze der Liebe by the Munich Film Museum, now allow for a more detailed account of their political challenge than was available to Dyer. While by no means revealed as a smash-the-state work, Gesetze’s very queer attitude to laws – whether of nature or human legislation – is far more visible due to the painstaking reconstruction of the documentary through the interpolation of material from surviving yearbooks of Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexology. The survival of a partial print of Gesetze der Liebe with Ukrainian titles also made possible the restoration of Anders, as the documentary included a cut of the earlier fiction feature as its rousing, closing case study. Not only is this a unique film history, but a decidedly queer one, as Hirschfeld worked by hook or by crook – to borrow the title of Silas Howard and Harry Dodge’s 2001 buddy movie, widely regarded as the first narrative fiction feature film by an out trans director – to pursue his fight for gay rights by cinematic means.

Dr Magnus Hirschfeld introduces the edit of Anders als die Andern (1919), which includes the documentary footage of LGBTIQ+ balls that led to its censorship, within his lecture-documentary Gesetze der Liebe (1927).© Filmmuseum München DVD, 2021.

While the case for Anders as both a key Weimar film and a key queer film has been well-established since Dyer’s definitional article, the restoration of Gesetze makes it possible not only to emphasize its queerness by examining its enrolment within a campaigning documentary that goes beyond the simultaneous paternalism and voyeurism associated with the Aufklärungsfilme, the social problem films with which Dyer classifies Anders, but to consider how a scientific documentary might be a ‘borderline case’ the expands the definition of Weimar cinema beyond the narrative fiction feature, and beyond the borders of Germany in ways that are particularly queer, and resonate with the experience of queer Jews such as Hirschfeld who became a refugee after 1932. Thinking with Hirschfeld’s internationalism – itself considered a suspect and entartung characteristic by National Socialism as by conservative forces elsewhere in the world – I will add another ‘borderline case’ to Dyer’s account of queer Weimar cinema: Borderline (1930), a film made in Switzerland by three writers, two British and one American – Bryher, Kenneth MacPherson and H.D. – and starring American actors Paul and Eslanda Robeson. The trio collectively called themselves the POOL Group, and their radical film journal Close-Up was an early English-language champion of Weimar cinema, and particularly the work of G.W. Pabst. Both Gesetze and Borderline differently absorb the Stimmung of Expressionism across modes, forms and national borders, and reflect back the queerness of Weimar aesthetics as politicised and politicising in Walter Benjamin’s sense.[7]

Pabst’s own Die Büsche der Pandora (1929), an avowed influence on the POOL Group, is in its own sense a ‘borderline case’, far from open-and-shut in terms of its evaluation as queer cinema. As Pamela Hutchinson explores in her 2017 BFI Film Classics re-evaluation of the film that followed its restoration by Martin Koerber, and spearheaded by David Ferguson and Angela Holm, the film’s ambiguity and polyvalence with regards to gender and sexuality is paralleled by that of the competing narratives of its making (as well as the multiple censored prints in which it survived to the present); privileging the queerly unreliable memoirs of its star Louise Brooks, Hutchinson attends to this rich polyvalence and ambivalence about the film’s genesis, narrative and intentions as a way of affirming its key role in Weimar film history and practice.[8] This determined indeterminacy, just as much as the dance between Lulu and Countess Geschwitz cut by the British Board of Film Censorship, becomes a hallmark of what a queer cinema might be, and how it might elude borders and laws as Lulu and her crew attempt to do.

Lulu and the Countess exchange “optical allure” before dancing at Lulu’s wedding, Die Büsche der Pandora (1929).

Some Gay Scenes

Lotte Eisner gets so close – yet remains so far – from a queer read on the aesthetics and narrative principles of Weimar cinema in The Haunted Screen, writing that “In the English review Close Up, which so ardently championed Pabst’s films in the thirties, a critic claimed that ‘Pabst finds the other side of each woman.’ ”[9] Eisner is paraphrasing a repeated refrain that cuts across H.D.’s long 1929 article on Pabst, “An Appreciation,” in which she recounts a coffee date with Pabst in Berlin the day after the premiere of “the much-delayed Pandora… at the Gloria Palast,” which the writer could not attend. She thus remarks that:

Louisa (as he calls her) Brooks, yes, she has a hidden side, a strange quality. If the film is any good at all it is obvious is going to be because Louisa Brooks has a strange quality … “There is another side to her.”

… But who (I may at this moment be permitted forensically to ask) would ever discover, could ever have discovered that “other side” but the perfectly preposterously modest director who sits facing us? “Louisa” Brooks has another side to her. So, obviously, has Greta Garbo, [Asta] Nielsen, the beautiful, the more than beautiful Brigitte Helm, the calm-eyed Herthe van Walter, and the demure, delicious little Edith Jehanne.

All the women of Herr Pabst’s creation, be it a simple super in a crowd scene, or a waitress in a restaurant, have “another side” to them.[10]

H.D. then repeats this claim with a slight variation after extolling “Garbo, under Pabst, [as] a Nordic ice-flower” (quoting her own earlier review essay on Die freudlose Gasse [Pabst, 1925], grandly titled “The Cinema and the Classics 1: Beauty” that opened Close Up’s first issue) and “Brigitte Helm, who is always an artist.”[11] Observing the difference between Garbo’s performance for Pabst and her “house-maid at a carnival” in the American Tolstoy adaptation Love (Edmund Goulding, 1927), H.D. opines that “Pabst is a magician, his people are ‘created, not made”? There is indeed ‘another side’ to every one of his women, whether it be the impoverished little daughter of post-war Vienna [as played by Garbo in Freudlosse] or one of the extras in an orgy scene, each and every one is shown as a ‘being’, a creature of consummate life and power and vitality. G.W. Pabst brings out the vital and vivid forces in women as the sun in flowers.”[12]

Eisner’s slightly contemptuous condensation cannot hear the dual or intertwining forces of H.D.’s ecstatic reception of Pabst’s work: she was, when not writing about film, a poet whose work was often concerned with the “vital and vivid forces of… flowers” as the first proponent of Imagism. She was also about to undergo a training analysis with Sigmund Freud (about which she would write Tribute to Freud), having previously been a patient, friend and kink partner of Havelock Ellis, as Susan McCabe explores in her joint biography of H.D. and her lover Bryher. H.D. was also queer, having lovers of multiple genders including her long-term relationship with Bryher who variously identified as a “girl-page” and, as per a letter to H.D. about a consultation with Ellis:

We agreed it was most unfair for it happen but apparently I am quite justified in pleading I ought to be a boy – I am just a girl by accident… I wanted to know why the universe was narrow-minded… I protested I had sat in a library so long I was afraid to get up and he asked me where my sense of adventure was. So I was silent.[13]

Bryher would go on to predominantly use he/him in letters to H.D. and to his husband and beard Kenneth MacPherson. Together, through their work in poetry, film, psychoanalysis and spiritual practices, H.D. and Bryher would explore “another side” to being assigned female at birth in multiple ways – not least, as is audible in H.D.’s litany of Pabst’s stars, a queer erotic inspired by the cinema screen that offers “the beautiful, the more than beautiful.” It’s also hard not to hear a prefiguration of Simone de Beauvoir’s famous statement that “a woman is not born, but made” in H.D.’s nuanced reading of Pabst’s direction of characters as “ ‘created, not made’,” emphasising a collaborative co-creation between performer and director but also – or even referring to or rooted in – the malleability of gender as highlighted by screen performance.

Eisner valuably captures, even as she somewhat dismisses, the striking emergence of a queer film criticism in parallel to a queer cinema, via Close Up, a journal that ran from 1927 to 1933, when Bryher – a queer Jew – fled the Nazi occupation of Berlin, and abandoned cinema. Like so many of the films it idolised, the little magazine was not available (outside a few academic libraries) until James Donald, Anna Friedberg and Laura Marcus anthologised some key contributions from across its run in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism in 1998. Despite co-inciding with the queer revitalisation of Weimar cinema scholarship, the collection makes little mention of queerness beyond identifying the complex relationship between its editorial ménage-à-trois. It also omits Close Up’s key work on racism in American cinema as well as the contributions of Modernist poet Marianne Moore, whom Ryan describes as possibly asexual and certainly genderqueer; Moore, Ryan notes, was entirely addressed by he/him pronouns in surviving letters from his mother and brother.[14] But the full extent of H.D.’s delirious homage to Pabst resonates with the female fandom of women stars that Jackie Stacey, in Star Gazing, and Diane Anselmo in her forthcoming A Queer Way of Feeling: Girl Fans and Personal Archives of Early Hollywood, valuably unpack as precursors to more recently-articulated forms of queer and trans writing about/of recognition through screen representation.[15]

Eisner cannot read (nor ‘read’ in the drag sense) H.D.’s articulation of recognition of her own desires and self-fashioning in the “vital and vivid” female characters and stars of Pabst’s oeuvre, and particularly their polyvalence and self-creation. Similarly, she both captures and misses the queerness of Mädchen, in a dismissal that will become definitive until Rich’s re-visioning in 1981. She notes that the film undeniably represents same-sex desires, but these are the “rather troubled atmosphere of close friendships between young adolescents, whose senses have still to come to rest on an object different from their own sex.”[16] Just a few lines later, however, she celebrates a “few gay scenes in Mädchen in Uniform [that] attest to the freshness which speech can bring to the image.”[17] This is of course a felicitous ambiguity of Roger Greaves’ English translation from the original French, but by 1969 the double meaning of ‘gay’ was out in the open. Eisner attributes both the dynamic aural qualities of the film and its atmosphere to first-time director Leontine Sagan; to her experience in theatre (Sagan had directed the Christa Winsloe play on which the film was based), in the first instance, and to her “feminine reading of the Kammerspielfilm” in the second.[18] As Dyer explores, there is a suggestion that a “feminine” film or reading thereof cannot be lesbian, as lesbianism is associated, especially by late Weimar, with figures who might be described as masculine, butch or inverts.[19]

Yet as a brilliant critic, Eisner identifies exactly that which makes the film “gay”: “the freshness which [sound] can bring to the image.” Mädchen was a major inspiration for Adam Zmith and I in developing our docufiction podcast about a lost experimental Weimar film, called The Film We Can’t See, released via BBC Sounds and broadcast on BBC Radio 4Extra in 2022. As well as its dynamic dialogue, which has been informed by Max Reinhardt’s freeing of actors from declamation, and been liberated by the boom mic from the stilted exchanges of early sound film, Mädchen uses sound queerly to make the film resonate as if it were the inside of a body. Eisner points particularly to the harmonics of “the flush of love trembling in the cracked voice of the adolescent – Hertha Thiele [Manuela] – in a counterpoint with the contralto of Dorothea Wieck [Fraulein von Bernburg].”[20] Thiele is distinctly femme in appearance, but she possesses a surprisingly deep, honeyed voice, one that grows louder as she plays the hosenrolle of Friedrich Schiller’s Don Carlos in the school play. Sound, costume and embodied performance are entwined as signs and sites of queerness and resistance, from Ilse tucking a smuggled letter into the maid’s bodice to the girls swooning at von Bernburg’s kiss while in their white nightgowns, or falling silent in the presence of the Princess after they have donned their formal dresses. At the end of the film, it is with uniforms askew and worn at night when they should be in bed, that Manuela’s dorm mates swarm the Expressionist main staircase, screaming for Manuela, and ringing the school bell on tiptoe. Previously, the geometric stairs with their echo of Nosferatu (FW Murnau, 1922) had been the site of Ilse warning Manuela about von Bernburg, Manuela ascending to von Bernburg’s study on two occasions, swooping up and down as her voice does – and also Ilse’s bored Sunday experiments with embodied sound, in which she first spits, and then throws snap-bangs, down the steep stairwell. In the Kino Lorber restoration of the film, if you listen carefully, it’s possible to hear the sound of Ilse’s spit as it lands: what a queer effect! It’s a detail as swoony as the EvB embroidered on nightgowns and written on skin.

As Chris Straayer observes in Deviant Eyes, Deviant Bodies, where they identify the film as a “typical baby butch fantasy,” “Ilse… although narratively heterosexualized, has the conventional markings of a baby butch (for example, dark hair, physical activity, body posture, tomboyishness)… And when E.v.B. slaps her on the buttocks, it is she [Ilse] who exhibits the film’s most explicit sexual response. Although not the main character, Ilse is the ringleader. Her agency lends Mädchen in Uniform a sexual logic without which its audience might only fantasize a platonic love.”[21] Ilse’s sexuality is loud: she encourages another girl to bust her buttons off her camisole with her breasts, and she declares her adoration for Hans Albers and his “sex appeal.” Fandom is linked to sound via sexuality: desire makes noise, and noise makes the film. As Dyer notes, Mädchen survived where Anders was almost erased, because of international fandom: while the film did encounter censorship in Germany, as well as notably in the U.K. and in Sweden, it was also rapturously received, winning an award for Outstanding Technical Achievement at Venice. Alongside critical acclaim, the film was the subject of one of the first documented queer teen fandoms, with life reflecting art as schoolgirls in Romania bought and wore black stockings in homage to Manuela’s Don Carlos, and causing the Romanian distributors to demand 20 feet more of kissing.

© Kino Lorber/BFI DVD. Manuela rehearsing as Don Carlos, with Ilse sitting at her feet.

These facts come from the long interview with Thiele by Karola Gramann and Heidi Schlüpmann for Frauen und Film in 1981, shortly after Rich’s reflection on Mädchen’s revival by the feminist film festivals of the 1970s. [22] Unlike several of her fellow cast members who were Jewish and queer (most notably Emilia Unda, who plays the authoritarian headmistress), Thiele remained in Germany and controversially worked on films made under Goebbels’ intervention into the German film industry. She survived the war, and in 1981 provided Gramann and Schlüpmann with unparalleled insights into the production and reception of Mädchen in an account that rivals Brooks’ writing on Pandora’s Box as a performer’s insight and creative archival source. It feels particularly fitting that the most detailed account of Mädchen should come from the performer whose character was the subject and mirror of the fandom that enabled the film to survive its Nazi ban; it was queer fans who responded to the “few gay scenes” on multiple levels, both hearing the sonic effects as Eisner heard them, and as she could not.

As Alice A. Kuzniar notes in the chapter on Weimar in her book The Queer German Cinema, Anders was also a film that operated through the phenomenon of subcultural fandom, with reception reflecting the representations on screen. The film “created for [Conrad] Veidt [who plays the protagonist Paul] a gay fandom: his subsequent appearances both onscreen and off were regularly announced and reviewed in the gay press; and Christopher Isherwood has recorded that Veidt was an idolized presence at one Berlin Christmas costume ball.”[23] This fan community surely shaded a contemporaneous apprehension of Veidt’s queerness – what Dyer calls his “seductive, sinister quality” – in Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920).[24] In the DVD liner notes for the Munich Film Museum release, Stefan Drössler notes that the film was “highly successful [in Berlin] and ran there for months. An unusually large number of copies were subsequently distributed throughout Germany” with enough public awareness that there were calls for a boycott, and local police in Munich, Karlsruhe and Stuttgart closed down screenings.[25]

This is in interesting contradistinction to the argument by Horak in an interview with Exberliner magazine marking the restoration’s screening at the 2016 Berlinale for the 30th anniversary of the Teddy award, that the film was primarily screened in director Richard Oswald’s own private cinema, and that “Anders als die Andern wasn’t hugely successful. And I am pretty sure that it didn’t play outside of the major cities. This isn’t a film that would have played in the suburbs, or in the country.”[26] It also acts as counterpoint to the all-too-brief mention of the film (and mainly of its censorship) in Charlotte Wolff’s exhaustive and brilliant biography of Hirschfeld.[27] Drössler establishes that the film was not just a countercultural artefact, but a cultural artefact with wide reach and a considerable impact, as well as – like Mädchen – a specific queer fandom that could ‘read’ the film in ways that straight viewers did or could not.

Famously, the film that pleaded for a change to the sodomy law inspired the Weimar Republic instead to introduce film censorship, beginning with a ban on this film. James Steakley argues, in “Cinema and Censorship in the Weimar Republic: The Case of Anders als die Andern,” that it was not Paul’s affectionate relationship with his student Karl nor his blackmail by his hook-up Franz that led to the calls for boycott and the ban, but rather it was cited for “dance scenes depicting anonymous members of the third sex.”[28] There are in fact two dance scenes in the film that show first Paul then Franz in queer environs: Paul is at a more upper-class costume party when he meets Franz, who is clearly cruising for marks; while later Franz is seen thinking through his blackmail scheme at a more working-class bar or party. In the first scene, the costumes are vibrant and suggestive of a ball; in the second, the drag cabaret life of the city is on vivid display. It would seem likely that the critique of the film relates to the latter not the former, and is as much a critique of class as gender and sexuality. What is an indulgence in private parties for the wealthy is to be deplored among the poor. Even a film that is imploring empathy for gay men parallels criminality and cabaret, parties and cruising. This association of gender/queerness and criminality is a manifestation of entartung, Friedrich Nordau’s influential eugenicist concept of degeneracy, which also pervades Pandora’s Box.

Anders sets Paul outside both these environs, while gaining aesthetic and dramatic power from depicting scenes and embodiments not previously seen on the fiction feature screen. Taking Steakley’s claim seriously, Anders stakes a strong claim to being the first film with trans, as well as gay male, representation. As in Mädchen, both sexuality and gender are inverted by the presence – the absent presence in Anders’ case – of sound. Kuzniar suggests that in fact it was some of cinema’s queerness, too, that was lost through the introduction of sound when she argues that “it is the body in silent cinema that must be allegorically read; through heightened facial features and hyperbolic gestures, the body betrays its passion and sensuality, with more than a hint of sexual deviance. Exaggeration shows it always already engaged in performance. Clothing, too, in its manifest exteriority, begs to be read as theatrical sign, hence the fascination of silent cinema with concealment and revelation, not infrequently involving cross-dressing.”[29] No wonder, then, that it is Mädchen (perhaps along with Josef von Sternberg’s films with Marlene Dietrich) that return queerness via a sonority linked to the concealment and revelation of costume, sound that drapes and lifts as a surface.

Hence it is fascinating that music is a defining feature of Anders, the way it conveys desire, danger and yearning. Kuzniar writes of the “optical allure” of silent film performers such as Anita Berber (who appears in Anders, although without her famed monocle and tuxedo),[30] but Anders, filmed entirely frontally in single-take scenes, situates its allure in what we cannot yet hear. The spaces of queer sexuality are limned by the unheard sound of dance music that is conveyed by the cavorting of the “anonymous members of the third sex,” and Paul is a violinist whose student Karl falls ardently in love while listening to him play. Even before synchronous sound was possible, Anders is feeling its way towards a queer future in which both sonority and homosexuality will reach their full and public expression. In Anders, homosexuality is precisely the love that cannot speak its name.

Which makes it all the more fascinating that the film is then recut into a second silent film, one that is very much about speaking: an unusual hybrid documentary called Gesetze der Liebe (1927), which is framed by the device of Magnus Hirschfeld delivering one of his famous lectures on sexual and gender variance among more-than-humans to argue that such variance is natural, too, among humans. As Drössler notes, Hirschfeld’s need to include Anders derived from its ban, and his ability to do so derived from the dissolution of Oswald’s production company in 1927, two frustrating outcomes for such an impassioned project.[31] Gesetze was not envisioned as a replacement for Anders: rather than being for theatrical exhibition, it was intended to accompany Hirschfeld on his lecture tours or even to replace him, as he had been the subject of violent attacks in the streets after his talks. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, Gesetze was banned due to its lack of “scientific objectivity” or “educationally deterrent message,” instead presenting LGBTIQ+ people as widely occurring throughout history, fully human and deserving of respect. This led the filmmakers to cut the inclusion of Anders for resubmission, which – with a further abridgement of the portion of the lecture on the work of the Institute – was approved for screenings to adults. Hirschfeld, ironically, then developed an additional live lecture portion that replaced the cut sections with a presentation of “static photographs,” and it was a record of these photographs, along with Hirschfeld’s published pamphlet of the film’s captions and the censorship files, that allowed Drössler and his team to reconstruct the film from the censored Ukrainian print. The addition, subtraction, and static presentation of “a few gay scenes” is what makes the documentary so crucial to film and queer history.

Borderline Cases

It is also, I want to argue, Gesetze’s nature as a hybrid of lecture, documentary and docufiction that makes it so valuable and compelling; in the final part of the film, Anders is presented as a lightly fictionalised case history (which may indeed be the case) of a talented middle-class musician who committed suicide after being blackmailed. It thus becomes a summative, supposedly scientific statement that follows the incredible early scientific documentary footage that Hirschfeld was able to source from the film’s producers, Humboldt Film, who the same year collaborated on Wie wohnen wir gesund und wirtschaftlich? (1927, How do we live healthily and economically?), the first documentary about Bauhaus architecture. Written by Ise and Walter Gropius, that film also survives only as fragments as Bauhaus was, like Hirschfeld’s institute and his idea of sexual liberation, seen by the Nazis as part of a Jewish agenda of cultural Bolshevism, and destroyed. Gesetze, too, would be seen as part of that same agenda as it made the case that human gender and sexual variance were not entartung, degenerate, but in fact part of the generativity of evolution and the diversity of the natural world.

Even for contemporary twenty-first century viewers, accustomed to HD 4K full-colour nature documentaries that employ microscopic cameras, drones and other feats of access to the natural world, Gesetze’s filmy black-and-white brief sequences shot in the laboratory include breathtaking close-up studies of insects and plants that remain striking in their sensitivity to balletic movement. Anticipating Cole Porter’s song of the following year, you will indeed see birds do it and bees do it, even hermaphroditic snails do it (one of the film’s most beautiful sequences), and – in a lyric that Porter could only have dreamed of being able to use – a spider that “copulates in a wedding palace built of air bubbles and silk strands.”

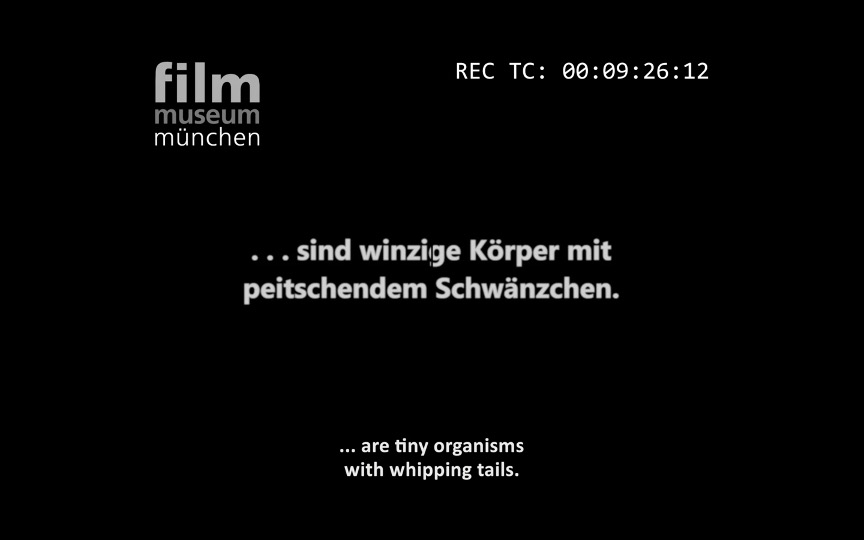

Hermaphroditic snails living their Cole Porter life in Gesetze der Liebe. Screenshot © Filmmuseum München. Gesetze der Liebe, 1927.

What could be queerer? In Gesetze the reference to the sonorous body manifests in the intertitles that capture Hirschfeld’s ornate and engaging public rhetoric, giving us a sense of his compelling speaking voice. Far from the deadly earnestness that one might expect from a campaigning documentary, Hirschfeld leads us through the recognisable conventions of Darwinian naturalism with reads that – like that spider – fulfil Susan Sontag’s definition of camp.[32] The intertitles change how we see the scientifically objective documentary footage, perhaps most of all in the sequence of moths and butterflies hatching their gauzy, gorgeous wings, which feels implicitly trans. One can also imagine the laughter from the parts of the audience who knew either Yiddish or low German – those who frequented the cabarets and bars where it was spoken – when Hirschfeld gives this vigorous description of mammalian sperm, which puns memorably on schwanz, slang for penis.

Screenshot © Filmmuseum München. Gesetze der Liebe, 1927.

Made out of a combination of canny opportunism and urgent campaigning necessity, Gesetze is a thing of wit and beauty, a film that opens up the canon of Weimar cinema queerly to argue for the inclusion of documentary – and the re-inclusion of Anders as a more visually inventive film that is often credited, as it is reverse-engineered to contain lab footage, diagrams, paintings and a lecture. The copulating spider and the hatching cocoons are both suggestive of the “shimmering phantasmagoria” that Eliza Steinbock reads as the origin point of a trans cinema in their book Shimmering Images: Trans Cinema, Embodiment and the Aesthetics of Change. In their first chapter, on early film and photomontage, Steinbock refers to Hirschfeld’s

“Yearbooks for Sexual Intermediaries” (1899–1923) [one of Drössler’s sources for the reconstruction], which consist of over 20,000 pages showing the variance of psychic and physical hermaphroditism, transvestism, and homosexuality between the poles of what he called the “full woman” and the “full man”… [Thus] framing… phantasmagoria as a cultural series has the benefit of bringing together, and thinking through, two historical transitional moments: when technological reproducibility first affected visual culture by heightening the volatility of the audiovisual image, and when surgical and sexological science also first acknowledged the mutability of gender.[33]

Steinbock cites as a key example of this phantasmagoria Lili Elbe’s pseudonymously-published photomontage autobiography Fra Mand til Kvinde – Lili Elbes Bekendelser (1931), a technological “shimmering” in which image and text modulate each other to create “a gendered embodiment that moves across the ‘abyss of man and woman,’ appearing textually in flickers on both sides of the chasm.”[34] Hirschfeld’s lecture-documentary-docufiction has a similar flicker effect, both in its reshaping of Anders as a kind of flickbook edit of the film, and in the interposition of camp intertitles into the scientifically objective Humboldt footage. Both gender/sexuality and cinema hover in the flicker, as the film turns them this way and that, assuring us it is natural to be both/and, to be other than even the otherness of this new medium.

Before we were able to see Gesetze, Adam Zmith and I imagined that Hirschfeld had been able to make another film, the titular film we can’t see. We imagined that it would be similarly hybrid, and might similarly have a Ukrainian connection – specifically, to Sergei Eisenstein, whose father was born in Kiev Oblast. Eisenstein famously wrote to Hirschfeld in a highly theoretical letter – at once closely- and overwrought – detailing his (or, as will become evident, their) thoughts on gender and sexuality, which they identified for themselves as “bisexual” in the then-contemporary sense that would parallel something between androgynous, genderqueer and non-binary.[35] For Eisenstein, this was correctly revolutionary, a Hegelian synthesis of binary gender.[36] But the two great radical thinkers’ paths never crossed in person (as far as we know – in the gap of documentation lies our docufiction), and Eisenstein and Hirschfeld did not collaborate on a film that might have synthesised the political “shock” of montage with Expressionist indeterminancy to create a shimmering potentiality with the added queerness of sonority (as Eisenstein was, at the time, trying to make their first sound film).

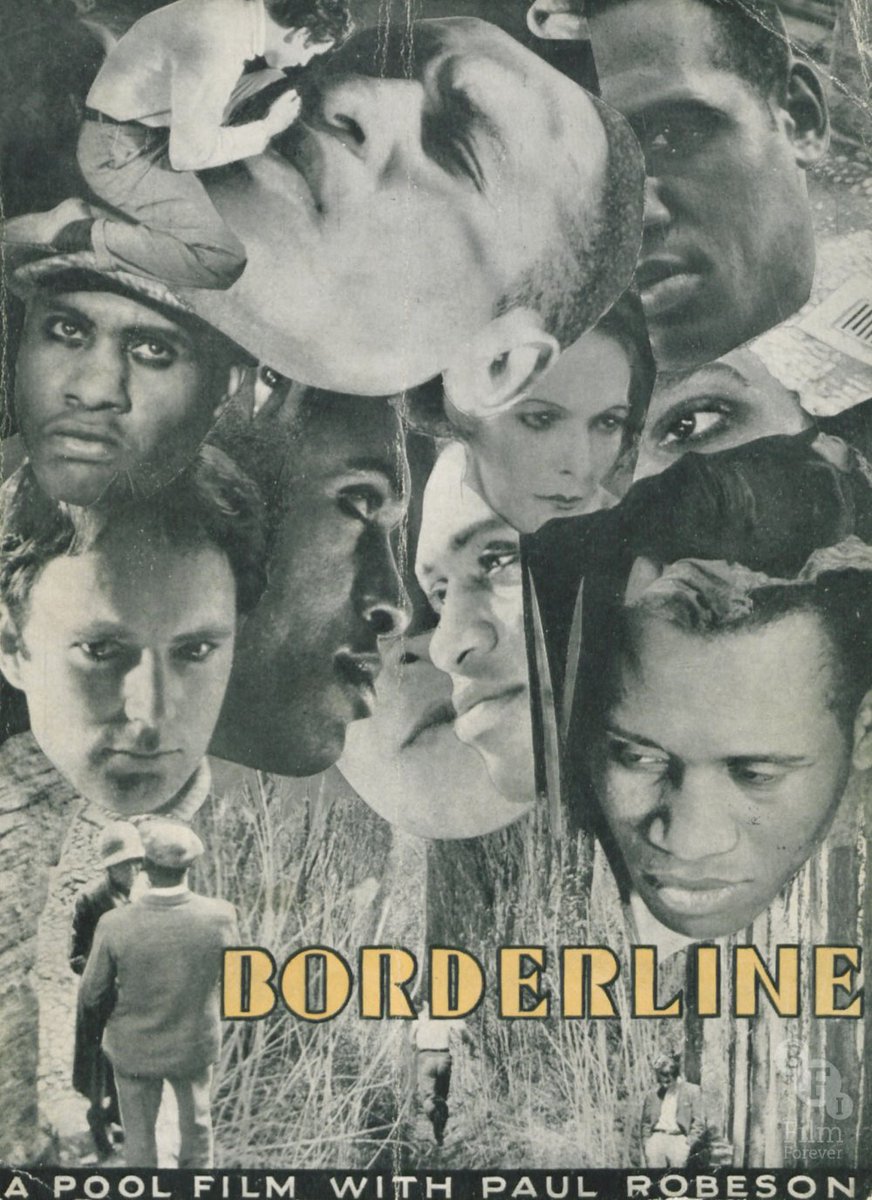

A precursor to that possibility that involves neither of those personnel does, however, exist – in the form of Borderline, which could be described as a Pabst-montage mash-up fanfic. As well as their homage to the German Expressionist, Close Up had published the English translation of Eisenstein and Pudovkin’s declaration on American sound cinema as a regressive move that stilted and nationalised the experimental possibilities achieved in a fluid, dynamic and transnationally-comprehensible silent cinema. In Berlin in 1927, meeting Pabst for the first time, Bryher and MacPherson also saw films by Eisenstein and Pudovkin before they were censored;[37] and which could not be seen at all in England because all Soviet films were banned to prevent them from causing a workers’ uprising.[38] Borderline would fall foul of the American censors for “foregrounding miscegenation,” due to the affair between Adah and Thorne, four years before the Hays Code was officially implemented.[39] The film’s queerness – including Bryher as a butch bartender, and gay actor Robert Herring (who had a crush on MacPherson) longingly throwing looks at Robeson (on whom MacPherson had a crush) – undoubtedly went unnoticed.

Pete in Borderline was Robeson’s second lead role, after the dual role of Isaiah and Sylvester in Oscar Micheaux’s Body and Soul (1925), and his second romantic lead, in a rare film to feature a mixed-race romantic relationship (Pete’s wife Adah was played by Paul’s wife Eslanda) as well as a Black male character with complex subjectivity and subtle emotional range. Eslanda Robeson’s biographer Barbara Ransby notes that Adah, too, was a multi-faceted role that “allwed Essie to be expressive and to showcase her natural talent” in her first on-screen role.[40] The film casts a light on the whiteness of Weimar cinema, which never made room for either Robeson, despite Paul being one of the most talented screen performers of the time and the presence of multiple Black communities in Berlin,[41] including the jazz scene presented by Esi Edugyan in her 2011 Weimar-set novel Half Blood Blues.[42] A leftist activist who took the opportunity of appearing in Showboat in London to study Swahili at SOAS, where he became involved with the Community Party, Robeson was also in touch with Eisenstein. They planned to work together, with mooted projects including a film about the Haitian Revolution, drawing on John W. Vandercook’s novel Black Majesty, a film that truly would have revolutionised cinema and whose loss is beyond tragic.[43]

Borderline, an avant-garde film that centres Stimmung within H.D. and Bryher’s editing practice, informed by Soviet cinema, of “clatter montage… meticulously cutting together of three and four and five-inch lengths of film,” is a “borderline case” for what could have been in terms of Robeson’s European film career as well as queer Weimar cinema, standing at the nexus of the two, almost unseen.[44] Sukhdev Sandhu describes Robeson as the film’s signifier of “liquid modernity,” a character whose physical and emotional mobility contrasts with the static white characters trapped in their mountain town and their hysteria.[45] But it was his star casting and international mobility that led to the film’s censorship and disappearance.

© BFI Archives. POOL Group poster for Borderline screening, probably for its premiere at the Academy Cinema, London, October 1930.

It was only with the resurfacing of Close Up that Borderline began to make its way back into film scholarship. Its 2006 restoration by the George Eastman House, sponsored by the British Film Institute as part of their Black World” project,[46] led to an event at Tate Modern Gallery curated by Karen Alexander, premiering the soundtrack composed for the restoration’s DVD release, by British jazz musician Courtney Pine. Pine’s Afrofuturist recasting back in time to create the jazz that cannot be heard in the bar where Borderline’s narrative takes place – doubly cannot be heard because it is a silent film, and because the town and its people are racist – marks the queer place of music in the film, and became the sonic thread of The Film We Can’t See, a reminder that histories of Weimar cinema are still being constructed as archival material, both cinematic and critical, comes to light and is restored and reinterpreted. Pine’s exuberant celebration of Robeson, the consummate screen intelligence of the era, offered us a way of doing more than grieving the work that was lost or celebrating the work that survived: of thinking into the gaps, and refusing the hard borders between past and present to follow queer Weimar cinema’s defiance of laws, nationalisms and fascisms.

Pete and Adah almost get free, walking in the mountains before confronting racist accusations in the bar, observed by the queer pianist and bartender in Borderline, POOL Group, 1930. © BFI DVD, 2007.

Already Going Into Exile

Film could only go so far. In the final issue of Close Up, published in June 1933, Bryher wrote an extraordinary editorial that is worth quoting at length, for its ferocious documentary account of summer 1932 in Berlin as it changed from his city of cinematic dreams to one of nightmares:

A year ago this June I returned from Berlin. I came from a city where police cars and machine guns raced about the streets, where groups of brown uniforms waited at each corner. The stations had been crowded: not with people bound for the Baltic with bathing bags, but with families whose bundles, trunks and cases bulged with household possessions. (The fortunate were already going into exile.) Everywhere I had heard rumours or had seen weapons. Then I crossed to London and to questions “what is Pabst doing now” or “will there be another film like Mädchen in Uniform?” I said “I didn’t go to cinemas because I watched the revolution” and they laughed, in England.[47]

Even in 1933, Bryher knows that Mädchen, which held such promise for him and many people like him, would come to stand for the fate of the queer community it depicted. Unlike the newspapers of the day, constrained by government oversight or shaped by their owners’ fascist leanings, Close Up is able to speak the truth: “Tortures are freely employed… Hundreds have died or been killed, thousands are in prison, and thousands more are in exile. A great number are Jews… In the future no Jew is to have the rights of an ordinary citizen.”[48] Bryher, whose father was Jewish, states the existence of “concentration camps,” whose existence would be ignored by the Allies for some time, and that artists and intellectuals are seeing their works burned and banned, and themselves exiled; Pabst “has been exiled… All his films have been banned in Germany.”[49] These are the only italics in the piece, the sense of incredulity that the filmmaker he worshipped has been targeted.

At the end of the editorial, Bryher suggests a way in which the queer social(ist) formations produced by the transnational cinematic experiment supported by Close Up could in fact be the foundation for political activism at this urgent moment. He closes:

In the choice of films to see, remember the many directors, actors and film architects who have been driven out of the German studios and scattered across Europe because they believed in peace and intellectual liberty.

The future is in our hands for every person influences another. The film societies and small experiments raised the general level of films considerably in five years. It is for you and me to decide whether we will help to raise respect for intellectual liberty in the same way, or whether we all plunge, in every kind and colour of uniform, towards a not to be imagined barbarism.[50]

It's hard not to shiver with prescience, both at Bryher’s uncompromising acknowledgement of a situation in Germany when Clement Attlee, as Britain’s Labour Prime Minister, would pursue appeasement from 1935 to 1938. Bryher is as much of a pacifist as Attlee, but he is thinking towards social formations that could secure peace in ways that would prevent Germany invading other countries and remove the National Socialist government, including raising awareness via transnational solidarity on the model of both experimental cinema and Hirschfeld’s development of sexology and LGBT+ rights. Bryher’s call to seek out films made by exiles as a political strategy resonates with contemporary conversations around film spectatorship and representation, on seeking out marginalised filmmakers and films. It is also a prescient insight into the considerable influence that Weimar’s filmmakers and technicians will have in exile, particularly but not only in Hollywood.

Particularly in films made by and about queer people, Weimar cinema was already envisioning its own exile, through an implicit understanding that inverts were only provisionally citizens, excluded from full citizenship by laws that precluded them from living openly in their genders and sexualities. Paragraph §175’s criminalisation of gender and sexual diversity underscored the entartung association of criminality with queerness and genderqueerness, leading to the internment of queer and trans people in concentration camps. In Pandora’s Box, borders are crossed as queer behaviours take the characters beyond the nation-state; they are damned if they stay, and damned if they leave. In rejecting Prussianism, queer Weimar cinema imagines its own becoming-refugee status as an anti-German cinema. Nowhere is this articulated more clearly than in Mädchen, with its dual presentation of Schiller as a national poet acceptable to the headmistress, yet a Romantic whose words foster both desire and rebellion among the students. Prussianness, the film shows through many small details, particularly to do with food, begins at school, and regimented obedience (which leads to fascism and nationalism) has to be guarded against, not implemented, in education. As Dyer points out, the film is daring in its references to Prussianism, not least “the derogatory portrayal of the principal in Mädchen, which through the use of a familiar iconography of cane, medallion, and bearing evokes Frederick the Great, the embodiment of authoritarian rule.”[51]

Sound and solidarity defeat authoritariamism, Mädchen in Uniform, 1931. © Kino Lorber/BFI, 2021

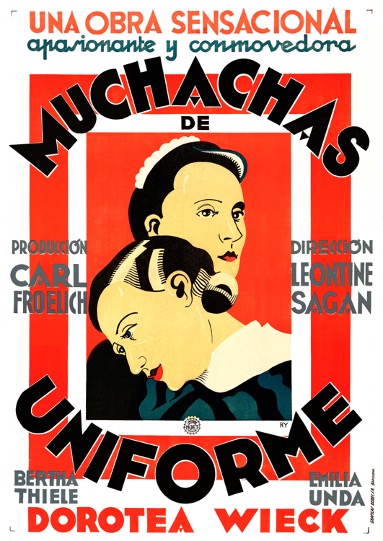

At the end of the film, she limps, defeated, into the depth of field of a long, empty hallway, in silence bar the tapping of her cane. Silence belongs to the old order. In the film, the most dramatic sound emerges precisely at the moment that von Bernburg dares to defy the headmistress and speak the name of her love, “Manuela!”, producing a cross-fade between their faces. Sound, in its most important function, crosses and even erases borders, as between the hall and the kitchen and the headmistress’s parlour as the girls’ post-show party resounds through the school, drawing the headmistress into the confrontation with Manuela’s desire that will bring her down. Sound is the radical force, almost Bolshevist, that breaks barriers and changes power dynamics. It’s perhaps no wonder that Republican Spain regarded the film as “una obra sensacional, apasionante y conmovedora,” as the Spanish poster in anarchist colours proclaims, the red geometric design echoed in Manuela and von Bernburg’s startling and sassy red lipstick. Just as sound is palpable in queer silents such as Borderline and Anders, so the sensuality of colour is vibrating in the monochrome world of Mädchen, a dream-image of life outside school and its grey-and-black striped uniforms and chessboard marble floors.

© Cinematerial. Spanish poster for Mädchen in Uniform.

Mädchen is not considered an Aufklärungsfilm, although its campaign for boarding school abolition and queer inclusion is of a piece with the earlier genre; what it deliberately lacks is their tragic ending. By 1927, Hirschfeld is also rejecting that narrative conceit (also visible in Pandora’s Box), by recutting Anders into a new film that ends not with Paul’s suicide but with Herr Doktor Hirschfeld vigorously shaking the hands of all of the audience members who have attended his lecture, a canny reflection of the reception he hopes will kinesthetically transmit to the offscreen audience the film imagines, but barely got to receive. In an equally canny strategy, albeit one that continues to vex LGBTIQ+ communities, Gesetze argues that what it calls “nature” should be shaping both medical care and, through the paternalistic intervention of scientists, legislation around gender and sexual diversity and equality. But the film escapes its didactic modality, as the interrelation of image and intertext invests in the laws of love as a cinematic style: an aesthetic, a pleasure and a set of gestures that make art through sex and community, shimmering phantasmagoria of potentiality.

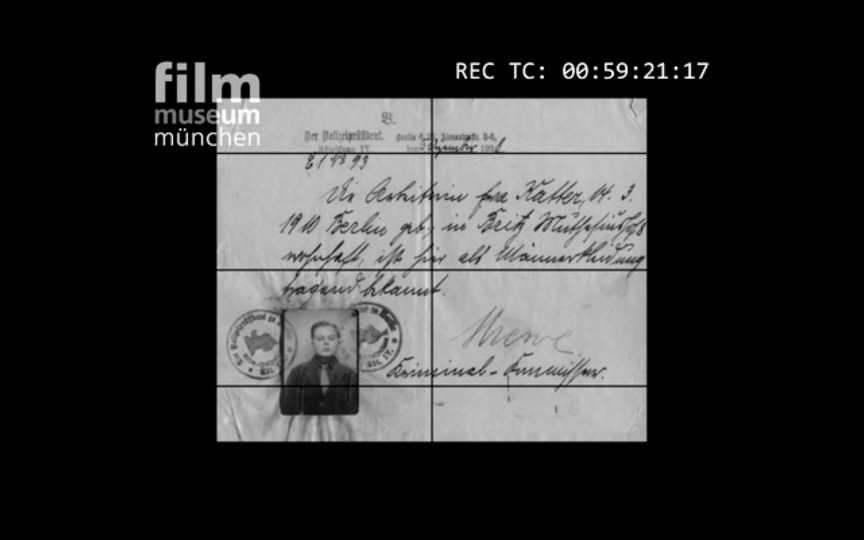

Screenshot © Filmmuseum München. Gesetze der Liebe, 1927.

Hirschfeld knew that visual images could make social and legal change. One of the most poignant inclusions in the restoration is the image of one of the ID cards issued by the Institute to trans people in Berlin to prevent their arrest for cross-dressing. Yet, as seen Joey Soloway’s television show Transparent which visits the Institute in a series of flashbacks in Season 2, the shimmering image met its limit with the ascent of National Socialism; Soloway’s imagined Jewish trans character Gittel cannot leave Germany with her mother and sister unless she is willing to travel under her assigned name and gender; her Hirschfeld card will not count as transit papers. By the time Bryher left Berlin in 1932, Hirschfeld himself knew he would never return from his triumphant world tour. He died in exile in Nice in 1935, having watched all the materials he had collected at the Institute burn when he accidentally saw a Pathé newsreel of the fires in Opernplatz in May 1933 when he stopped into a Parisian cinema. Like Pabst and Sagan, he had been part of a radical cinema that defied national borders and Prussian militaristic nationalism, and fought against legal constrictions rather than conforming to them: a cinema so provocative that it shaped the fascism that would follow, that precisely abhorred borderline cases and ambiguities, that would begin its reign of terror by burning Anders als die Andern in front of the Opera House, silencing the queer music that was just beginning to be heard on screen.

Dr. So Mayer is the author of three books on film: The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love (Wallflower, 2009), Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema (IB Tauris, 2015), and A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing (Peninsula Press, 2020), which was the seed for the BBC Sounds podcast The Film We Can’t See (2022), written and produced by Adam Zmith, on which they were a researcher and presenter. So is a member of queer feminist film curation collective Club Des Femmes, and a co-founder of campaigning organisation Raising Films.

References

[1] Richard Dyer, “Less and More than Women and Men: Lesbian and Gay Cinema in Weimar Germany,” New German Critique, 51, Special Issue on Weimar Mass Culture (Autumn 1990): 5-60. https://doi.org/10.2307/488171.

[2] B. Ruby Rich, “Maedchen in Uniform: From Repressive Tolerance to Erotic Liberation,” 24-25 (March 1981. https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC24-25folder/MaedchenUniform.html: para 7.

[3] Sadly the journal itself has been discontinued and the website taken down, but its editorial aims and Issue 1 table of contents can be found on its crowdfunder: https://chuffed.org/project/invert-journal.

[4] Hugh Ryan, When Brooklyn Was Queer (New York: Macmillan, 2019); Kit Heyam, Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender (London: Basic Books, 2022).

[5] Dyer, “Less and More”: 19–29; Magnus Hirschfeld, Berlin’s Third Sex, 1904, trans. James J. Conway (Berlin: Rixdorf Editions, 2017)

[6] Florence Ashley, “Queering Our Vocabulary – A (Not So) Short Introduction to LGBTQIA2S+ Language,” Medium.com, trans. Florence Ashley, Aug 7, 2018, https://medium.com/@florence.ashley/queering-our-vocabulary-a-not-so-short-introduction-to-lgbtqia2s-language-997ca6c8b657.

[7] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (London: Fontana, 1992), 234.

[8] Pamela Hutchinson, Pandora’s Box (Die Büsche der Pandora) (London: BFI/Bloomsbury, 2018), 1–10.

[9] Lotte M. Eisner The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, trans. Roger Greaves (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969), 296.

[10] H.D., “An Appreciation,” Close Up 4, no. 3 (March 1929). Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, eds. James Donald, Anna Friedberg and Laura Marcus (London: Cassell/Princeton NJ: Princeton Unviersity Press, 1998), 143.

[11] H.D., “An Appreciation,” 144, 145; H.D., “The Cinema and the Classics I: Beauty,” Close Up 1, no 1 (July 1917). Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, 105–109.

[12] H.D., “An Appreciation,” 145.

[13] Bryher to H.D., March 20, 1919, quoted in Susan McCabe, H.D. and Bryher: An Untold Love Story of Modernism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 74.

[14] Ryan, When Brooklyn Was Queer, 146–48.

[15] Jackie Stacey, Star Gazing: Hollywood Cinema and Female Spectatorship (New York and London: Routledge, 1993); Diane W. Anselmo, A Queer Way of Feeling: Girl Fans and Personal Archives of Early Hollywood (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2023).

[16] Eisner, The Haunted Screen, 326.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Eisner, The Haunted Screen, 325.

[19] Dyer, “More and Less,” 41–58.

[20] Eisner, The Haunted Screen, 326.

[21] Chris Straayer, Deviant Eyes, Deviant Bodies: Sexual Re-orientations in Film and Video (New York: Columbia UP, 1996), 124.

[22] Karola Gramann and Heidi Schlüpmann, “Hertha Thiele,” Frauen und Film 28 (1981): n.p. The interview is available in English translation and with an introduction by Leonie Naughton in Screening the Past 1: http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-1-classics-re-runs/madchen-in-uniform/. n.d.

[23] Alice A. Kuzniar, The Queer German Cinema (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2000), 28.

[24] Dyer, “More and Less,” 15.

[25] Stefan Drössler, “From Anders als die Andern to Gesetze der Liebe,” DVD booklet, Magnus Hirschfeld: Anders als die Andern und Gesetze der Liebe und Geschlecht in Fesseln (Munich: Filmmuseum München, 2021), n.p.

[26] Jan-Christopher Horak, “More Than Just 30 Years: Anders als die Andern,” Exberliner, Feb 11, 2016, https://www.exberliner.com/film/more-than-just-30-years-of-lgbt-film-anders-als-die-andern/.

[27] Charlotte Wolff, Magnus Hirschfeld: A Portrait of a Pioneer of Sexology (London, Melbourne and New York: Quartet, 1986), 190–91; 194–95.

[28] James D. Steakley, “Cinema and Censorship in the Weimar Republic: The Case of Anders als die Andern,” Film History 11, no. 2 (1999): 195.

[29] Kuznia, Queer German Cinema, 21–22.

[30] Kuzniar, Queer German Cinema, 21.

[31] Drössler, “From Anders,” n.p.

[32] Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’,” Against Interpretation and Other Essays, 1961 (London: Penguin, 2009), 275–292.

[33] Eliza Steinbock, Shimmering Images: Trans Cinema, Embodiment, and the Aesthetics of Change (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019), 31.

[34] Steinbock, Shimmering Images, 43; Fra Mand til Kvinde was translated into English and edited by Niels Hoyer as Man into Woman: The First Sex Change, A Portrait of Lili Elbe (London: Blue Boat Books, [1933] 2004).

[35] Evgenii Bershtein, “Eisenstein’s Letter to Magnus Hirschfeld: Text and Context,” in The Flying Carpet: Studies on Eisenstein and Russian Cinema in Honor of Naum Kleiman, eds. Joan Neuberger and Antonio Somaini (Sesto San Giovanni: Éditions Mimésis, 2017), 75–86.

[36] The possibility of offering an in-depth;’ sexual-dialectical reading of Eisenstein’s films as foundational to trans cinema and theory awaits its Cáel M. Keegan, whose Lana and Lilly Wachowski (Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 2018) has been formative for the field of trans (re)readings.

[37] McCabe, H.D. and Bryher, 134.

[38] Tom Dewe Mathews, Censored: The Story of Film Censorship in Britain (London: Chatto & Windus, 1994), 40–42.

[39] McCabe, H.D. and Bryer, 152.

[40] Barbara Ransby, Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson (Chicago: Haymarket Books [2013], 2022), 92.

[41] See 1914–1945 collection on Black Central Europe: https://blackcentraleurope.com/portfolio/1914-1945/.

[42] Esi Edugyan, Half Blood Blues (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2011).

[43] Ivor Montagu, With Eisenstein in Hollywood (Berlin: Seven Seas, 1968), 346.

[44] H.D., Borderline: A Pool Film with Paul Robeson (London: Mercury Press, 1930). Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, 230.

[45] Sukhdev Sandhu, “Borderline and the Emergence of Black Cinema,” in the DVD booklet for Kenneth Macpherson, Borderline (London: BFI, 2007), 14.

[46] Lucy Reynolds, “June 2005: Launch of Black World,” LUXOnline n.d., https://www.luxonline.org.uk/histories/2000-present/black_world.html.

[47] Bryher, “What Shall You Do In the War?,” Close Up 10 no. 2 (June 1933). Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, 306.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Bryher, “What Shall You Do,” 307.

[50] Bryher, “What Shall You Do,” 309.

[51] Dyer, “More and Less,” 38.

Bibliography

Anselmo, Diane W. A Queer Way of Feeling: Girl Fans and Personal Archives of Early Hollywood. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2023.

Ashley, Florence. “Queering Our Vocabulary – A (Not So) Short Introduction to LGBTQIA2S+ Language.” Trans. Florence Ashley. Medium.com, Aug 7, 2018. https://medium.com/@florence.ashley/queering-our-vocabulary-a-not-so-short-introduction-to-lgbtqia2s-language-997ca6c8b657

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, 211-244. London: Fontana, 1992.

Bershtein, Evgenii. “Eisenstein’s Letter to Magnus Hirschfeld: Text and Context.” In The Flying Carpet: Studies on Eisenstein and Russian Cinema in Honor of Naum Kleiman, eds. Joan Neuberger and Antonio Somaini, 75–86. Sesto San Giovanni: Éditions Mimésis, 2017.

Bryher, “What Shall You Do In the War?,” Close Up 10 no. 2 (June 1933). Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, 306–309.

Dewe Mathews, Tom. Censored: The Story of Film Censorship in Britain. London: Chatto & Windus, 1994.

Donald, James, Anna Friedberg and Laura Marcus, eds. Close Up: Cinema and Modernism. London: Cassell/Princeton NJ: Princeton Unviersity Press, 1998.

Drössler, Stefan. “From Anders als die Andern to Gesetze der Liebe.” DVD booklet, Magnus Hirschfeld: Anders als die Andern und Gesetze der Liebe und Geschlecht in Fesseln. Munich: Filmmuseum München, 2021.

Dyer, Richard. “Less and More than Women and Men: Lesbian and Gay Cinema in Weimar Germany.” New German Critique, 51, Special Issue on Weimar Mass Culture (Autumn 1990): 5-60. https://doi.org/10.2307/488171

Edugyan, Half Blood Blues. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2011.

Eisner, Lotte M. The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, translated by Roger Greaves. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969.

Gramann, Karola, and Heidi Schlüpmann, “Title”, Frauen und Film 28 (1981). Trans. Leonie Naughton, “Madchen in Uniform,” Screening the Past 1 (year): http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-1-classics-re-runs/madchen-in-uniform/

H.D. “An Appreciation,” Close Up 4, no. 3 (March 1929). Reprinted in Close Up, eds. , 139–148.

——. Borderline: A Pool Film with Paul Robeson. London: Mercury Press, 1930. Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, 221–236.

——. “The Cinema and the Classics I: Beauty,” Close Up 1, no 1 (July 1917). Reprinted in Close Up: Cinema and Modernism, 105–109.

Heyam, Kit. Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender. London: Basic Books, 2022.

Hirschfeld, Magnus. Berlin’s Third Sex. 1904. Trans. James J. Conway. Berlin: Rixdorf Editions, 2017.

Horak, Jan-Christopher. “More Than Just 30 Years: Anders als die Andern.” Exberliner, Feb 11, 2016. https://www.exberliner.com/film/more-than-just-30-years-of-lgbt-film-anders-als-die-andern/

Hoyer, Niels, ed. and trans. Man into Woman: The First Sex Change, A Portrait of Lili Elbe. London: Blue Boat Books, [1933] 2004.

Hutchinson, Pamela. Pandora’s Box (Die Büsche der Pandora). London: BFI/Bloomsbury, 2018.

Keegan, Cáel M. Lana and Lilly Wachowski. Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Kuzniar, Alice A. The Queer German Cinema. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

McCabe, Susan. H.D. and Bryher: An Untold Love Story of Modernism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Montagu, Ivor. With Eisenstein in Hollywood. Berlin: Seven Seas, 1968.

Ransby, Barbara. Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson. Chicago: Haymarket Books [2013], 2022.

Reynolds, Lucy. “June 2005: Launch of Black World.” LUXOnline n.d. https://www.luxonline.org.uk/histories/2000-present/black_world.html

Ryan, Hugh. When Brooklyn Was Queer. New York: Macmillan, 2019.

Sandhu, Sukhdev. “Borderline and the Emergence of Black Cinema.” In DVD booklet for Kenneth Macpherson, Borderline, 9–14. London: BFI, 2007.

Sontag, Susan. “Notes on ‘Camp’.” Against Interpretation and Other Essays, 275–292. London: Penguin, 2009.

Straayer, Chris. Deviant Eyes, Deviant Bodies: Sexual Re-orientations in Film and Video. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Stacey, Jackie. Star Gazing: Hollywood Cinema and Female Spectatorship. New York and London: Routledge, 1993.

Steakley, James D. “Cinema and Censorship in the Weimar Republic: The Case of Anders als die Andern.” Film History 11, no. 2 (1999): 181–203.

Steinbock, Eliza. Shimmering Images: Trans Cinema, Embodiment, and the Aesthetics of Change. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019.

Wolff, Charlotte. Magnus Hirschfeld: A Portrait of a Pioneer of Sexology. London, Melbourne and New York: Quartet, 1986.