Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

IF ONLY I HAD THE CINEMA!!

Hans Helmut Prinzler

“If only I had the cinema!!”– note the two striking exclamation points – was the title of a pamphlet by Carlo Mierendorff, published in 1920, a title that abides today as a topic of interest, as a headline, almost as a mantra. But we still have it, the cinema. We still have it. We just have to make sure that the day will not come when it suddenly disappears. And we must constantly bear in mind this resolve.

When Mierendorff penned his expressionistically inflected and carefully formulated appeal, the cinema was a mere 25 years old. Back then, in 1920, when Mierendorff's text appeared, there were 3,422 cinemas in Germany. And around 500 German feature films premiered that year in these cinemas. Not all were feature-length. And people said films (and not yet Filme) if they meant more than one. We also must not forget that the First World War had ended only two years before. The famous 1920s of the Weimar Republic was beginning. Among the 500 films from 1920 there are three that just about everyone in this room will know: THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI by Robert Wiene, THE GOLEM: HOW HE CAME INTO THE WORLD by Carl Boese and Paul Wegener and ANNA BOLEYN by Ernst Lubitsch. I will not assume that anyone - apart from Hans-Christoph Blumenberg, of course - has seen THE GIRL FROM THE ACKERSTRASSE by Reinhold Schünzel. Or Richard Oswald's THE-MERRY-GO-ROUND (REIGEN) with Asta Nielsen and Conrad Veidt. Of course, everyone here has seen Murnau's NOSFERATU, which was produced in 1921, a year later, and now belongs to the canon. Today screenings of this silent film are often accompanied by live music and reproduced in the lovely DVD editions that have become available. But even if we have DVD copies of old films one cannot help but wish: if only they had the cinema!!

If a book title from 1920 can inspire so many different thoughts, we are led to wonder: what does German film history teach us? What do we know about it? What about it is so beautiful and what is so terrible? How does German film relate to our political history, and to lessons that are of interest to all of us? And bearing in mind the unstinting arrival of new films, what do we do with the old ones? Apart from storing them in archives and preserving them there, assuming they are preserved at all.

I think that the passion for German film also includes a love of its history, even if that history has not and does not always make things easy for us. It is certainly much easier to stroll down a red carpet to the premiere of a new German film in Berlin, Munich or Hamburg and afterwards talk off the cuff about why things did not quite go as the director might have wished. Strong actors, an impressive camera, a good story, but somehow the film lacks – well, how to put it – depth and passion. Surely there is not enough there for a German Film Prize. And surely not enough for the film to be remembered three, five, ten or twenty years down the line.

The afterlife of films has become diminished. And for this reason, as film historians, we have the wonderful, sometimes arduous and not always fruitful job of constantly bringing to life films and their directors, actresses and actors, screenwriters, cinematographers, editors, scenographers, composers, and producers so that they might enjoy a semblance of immortality. After all, any film involves the work of many people. For its images, for its stories, for its creation and its long-term resonance, which is to say its posthumous presence.

To link memories of films with the present and also with the future, that would be, if only I had the cinema, my preferred vision. These days such an endeavor more often than not is described by such brittle terms as repertoire, media competence, film historical awareness, communal cinema, film canon, memory.culture. But in fact it is above all a matter of curiosity and desire, hearing and seeing, open eyes and open ears, of head and heart. Put precisely, it is a matter of passion. For the old and for the new. And for everything that helps to forge a connection between yesterday and today. We still have the cinema. Enter the cinema and let there be darkness. So that we might open our eyes. Because German film history is better than its reputation. As are German films. Or in any event, at the latest, they will be tomorrow, when all of today's resolves have found their fulfillment.

Berlin, German Film Academy / Academy of Arts, February 10, 2008

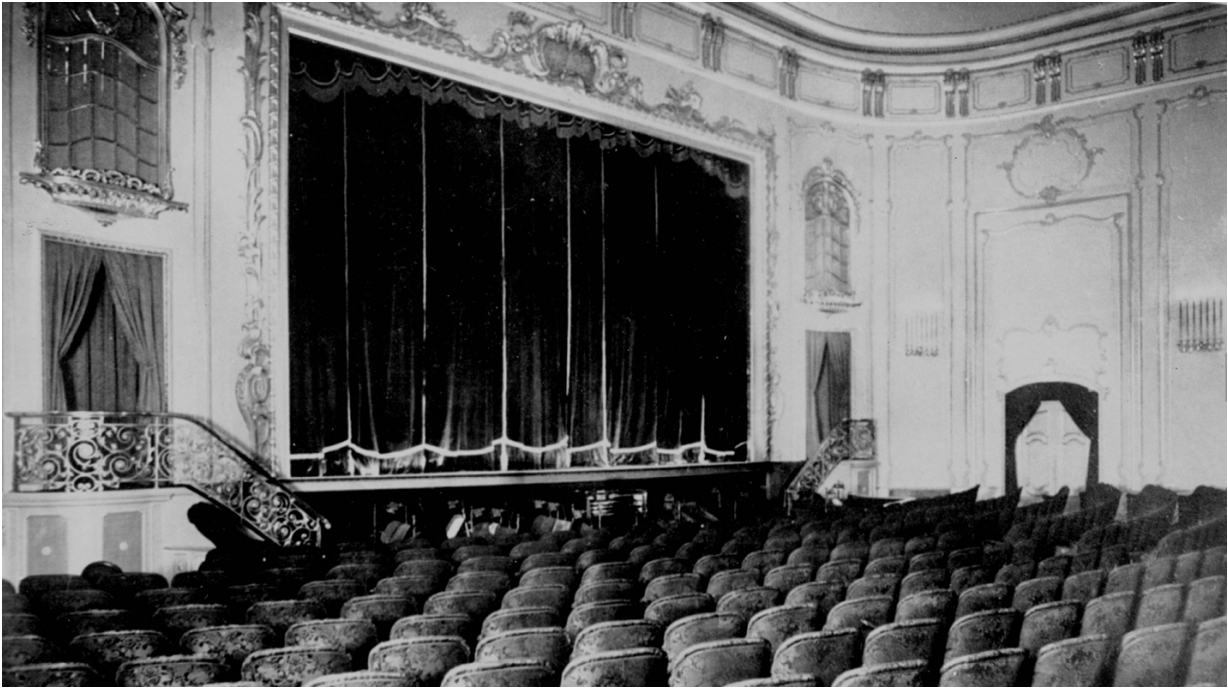

Gloria-Palast in Berlin, 1922

Titania-Palast in Berlin, 1928